David Sanderson, once a first-generation college student himself, brought his perspective and experiences to an Aspire Leaders Program Faculty Seminar. Now at the University of New South Wales, Sanderson continues to make an impact and instill community-based approaches across the world in development and emergency management.

For him and his elder brother, the children of a printer and housewife who both left school at the age of 14, education was an incredible privilege and formative opportunity.

After losing both of their parents within a few years during his preteen and early teenage years, he and his brother had the opportunity to attend grammar school. His parents saved money before their passing in order to send them to this state-funded school created for children who would not normally have access to this quality of education.

“I was very lucky,” Sanderson reflected. “I was the only person from my primary school to go to a different school [because] my parents sacrificed for me and my brother to do that. It would’ve been a different life.”

He was drawn to an undergraduate degree in architecture because of the combination of math and art.

“You get to learn about what you see in the world around you and how it’s made,” he said.

He went on to receive his master’s in development practice and a PhD in urban livelihoods and vulnerability – becoming the first in his entire family to pursue a third level of education.

Today, he not only teaches but also serves on several councils in Australia concerning bushfire recovery and has led various initiatives in global development at UNSW Australia.

A Journey to Impact

Sanderson’s master’s program at Oxford Polytechnic, now Oxford Brookes University, in 1991 expanded his view of the roles local voices can play in disaster relief, emergency response, and community development.

A professor in his department, Nabeel Hamdi, became a guiding force in Sanderson’s development and led him to explore research and disaster management.

“He was an architect, but he introduced us to the idea that the overwhelming majority of the world doesn’t get to engage with or interact with architects — and if you’re an architect working in a poor location, you’re probably one of the bad guys, coming in to knock local spaces down” Sanderson said.

It’s all about whose reality counts and tapping into local knowledge and needs.

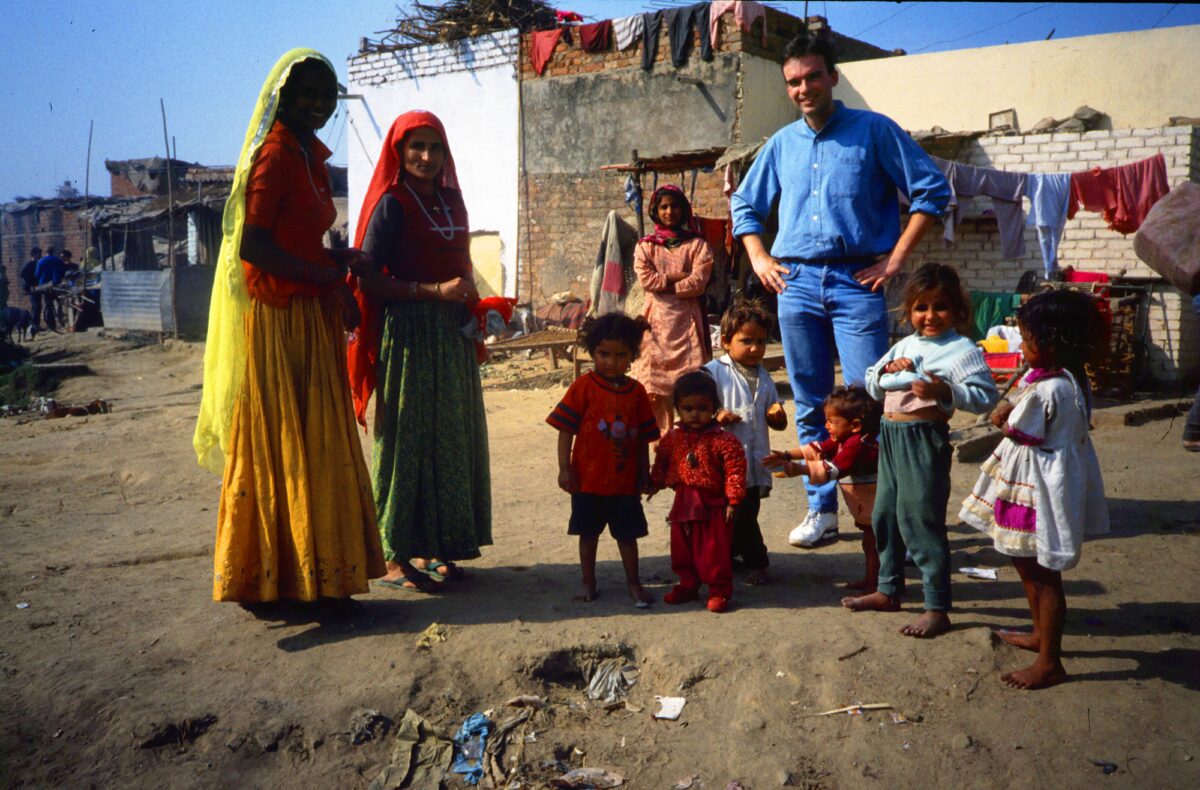

Working as a researcher for Hamdi gave him the opportunity to work for four years as a disaster management organizer in Eastern Europe, India, and Peru amongst other places. Going on the journey from architecture to disaster development changed his perceptions on the role an individual plays in community wide relief and resilience.

The key thing that Sanderson learned was to listen to the local voices on the ground.

“Who knows better than the local people,” Sanderson said. “It’s all about whose reality counts and tapping into local knowledge and needs.”

Sanderson agreed that the work that Aspire Institute does to support young leaders to make a change in their local communities and have a voice is incredibly important.

Stepping Into the Classroom

Sanderson did not always plan to become a professor or academician but feels proud to take on this role today.

Once stepping into the classroom when an opportunity arose at Oxford Brooks, Sanderson fell into a groove with academia, cherishing the opportunity to share his experiences, pedagogy, and lessons with a diverse group.

“Around the same table, you might have someone who grew up in a refugee camp, who served as a major in their country’s army, a fashion designer, an aid worker, someone new to the professional world who wants to change the world, and someone in the last chapter of their life,” he explained. “People of all ages, all backgrounds; it’s incredible.”

But building the bridge between practice and academic thinking and discourse took time, and is something many designers continue to struggle with today.

“I just wasn’t seeing a link between the work in the classroom and in reality: we can conduct blue sky research and propose ideas but if a program fails because the driver has malaria that day, then the project wouldn’t work,” he said. “If you aren’t aware of people’s realities then this is a pointless exercise.”

In addition to in-region research, Sanderson has dedicated time to disaster evaluation and relief: spending 2010 working on the earthquakes in Haiti; then Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines in 2013; and earthquakes in Nepal in 2016 with other small projects in countries like Pakistan.

“The privilege of doing that on-the-ground work is that you get to talk to the people actually overseeing the relief and recovery efforts and development; you can listen and learn,” he explained.

The Enjoyment of Working with Aspire Institute

This deep curiosity in understanding other people’s contexts and using them to make lasting change drew Sanderson to Aspire in the first place.

“Aspire is exciting to me because it really is engaging at the individual level, and changing people’s lives through education,” he said. “It’s the proven number one way to change the planet.”

Aspire is exciting to me because it really is engaging at the individual level, and changing people’s lives through education.

Education and giving a voice to others resonates with Sanderson as this is something he has also seen as driving factors to change throughout his work.

“Aspire is for people in remote and rural as well as urban and informal settlements who don’t typically get a chance at access, or the opportunity to share their own views and experiences,” Sanderson reflected.

Initially invited to facilitate a Faculty Seminar for the 2023 Aspire Leaders Program by Executive Director Meena Sonea, Sanderson shared that his short time with the students was deeply impactful.

“I was blown away,” he shared. “Sitting in front of 492 people, deeply engaged for 90 minutes [and] a conversation that was so rich. I’m not exaggerating when I say that it was the most powerful experience I’ve had, when it comes to teaching online.”